STORY CREDITS

Writer/Editor: Apeksha Srivastava

Photo: Media and Communication, IIT Gandhinagar

“If I were asked what is the greatest treasure which India possesses and what is her finest heritage, I would answer unhesitatingly that it is the Sanskrit language and literature and all that it contains. This is a magnificent inheritance, and so long as this endures and influences the life of our people, so long will the basic genius of India continue.” — Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister of independent India

The most ancient literary language of India, Sanskrit, is often called a “dead language.” The seventh edition of the Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) course at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar brought together scholars and practitioners to argue against this misconception and illustrate the strong and prominent survival of Sanskrit in our country’s cultural and social life. The experts highlighted this aspect through sessions based on Indian knowledge systems and traditions such as Ayurveda, performing arts, classical and regional literature, yoga, and intellectual and religious traditions, among other approaches.

Neither a Dead Language nor the Language of Gods

With a long list of accomplishments, Kapil Kapoor has been teaching for over sixty years and is one of the pioneers of the Indian Knowledge Systems in India. Starting his discussion with a common misconception of Sanskrit being a dead language, he explained that although it is not spoken in the streets today, it survives in various fields of knowledge in many ways and forms. Prof. Kapoor mentioned, “The Sanskrit language has been an indispensable instrument in forming the Indian worldview and cultural integration of the Indian subcontinent. I argue why the label of ‘language of the gods,’ sometimes stuck to Sanskrit, has failed to do justice to the intellectual traditions that grew around this language.”

Music and Poetics

Srinivas Reddy is a scholar, translator, and musician teaching at Brown University and IIT Gandhinagar. His talk emphasized how theoretical concepts, formulations, and frameworks derived from Sanskrit texts continue to shape the analysis and evolution of artistic disciplines such as music and poetics.

The talk viewed Sanskrit knowledge systems in a historical continuum, with particular reference to production, commentary, and translation as distinct modes of cultural influence. These highlight the enduring prestige of Sanskrit authority, the changing stature of Sanskrit influence, and the mutually interactive nature of theory with practice.

Sanskrit in Indian Education

A lifelong student of Indian civilization and the author of several books, research papers, and popular articles, Michel Danino is currently a visiting professor and co-coordinates the Archaeological Sciences Centre at IIT Gandhinagar. He shed light on the chequered history of Sanskrit in India’s educational system. While the Sanskrit Commission of 1957 made many recommendations to promote the teaching and learning of Sanskrit, it remained relatively minor in schools and higher education, hampered by vague notions of being irrelevant during present times or difficult to learn, among other reasons. Although the 1994 judgment of the Supreme Court laid the last preconception to rest, it has been argued that wrong pedagogies have done students of this language a disservice, apart from the systemic challenges. The lecture examined Sanskrit’s place in India’s current National Education Policy and discussed its future in global education.

Panchatantra

Raghavasimhan Thirunarayanan, a scholar-in-residence at IIT Gandhinagar, is associated with the History of Mathematics in India (HoMI) project. His session began with an introduction of how the seed of Sanskrit has grown over nearly two millennia and is still growing into a wondrous banyan tree of fables called the Panchatantra. According to Dr. Thirunarayanan, “Apart from a few religious texts, no other work has been translated and re-translated into as many languages as the Panchatantra. What is equally astounding is that these fables seem to fit the moral beliefs of many cultures even today.” The session discussed how the transmission of these Indian fables to many other cultures shaped the minds of young and old alike and illustrated the similarities and differences between the different versions of the tales using visual aids.

Sanskrit and Storytelling

Arupa Lahiry, a senior disciple of Smt. Chitra Visweswaran of Chennai, is impaneled with the Indian Council of Cultural Relations, Doordarshan, and the Ministry of Culture (Government of India). Her talk looked at some fundamental aspects of storytelling, or Kathaa Vaachana. An intrinsic part of Indian art and culture, Kathaa Vaachana is a tradition considered to be rooted in Sanskrit. Ms. Lahiry focused on some crucial questions: From grammar to content, how much of these regional practices are derived from the Sanskrit treatise and texts?

Do they still adhere to the specific regulations of the language, or have the regional nuances molded them differently? Accompanied by footage from real performances, the talk revolved around two forms of storytelling, from Kerala and Assam.

Koodiyattam

Ankita Nair, a Ph.D. scholar in Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Gandhinagar, has been working on Koodiyattam, a Sanskrit-based performing art form of Kerala. Her lecture explored how Koodiyattam combines Sanskritic and regional traditions, especially in terms of its literature and theatrical techniques. Ms. Nair expressed that while the tradition of staging Sanskrit plays continues even today, we see a backflow wherein artists translate Malayalam texts to compose Sanskrit verses. In essence, Sanskrit remains at the core of this art form either way. The lecture also discussed the survival mechanisms of this art.

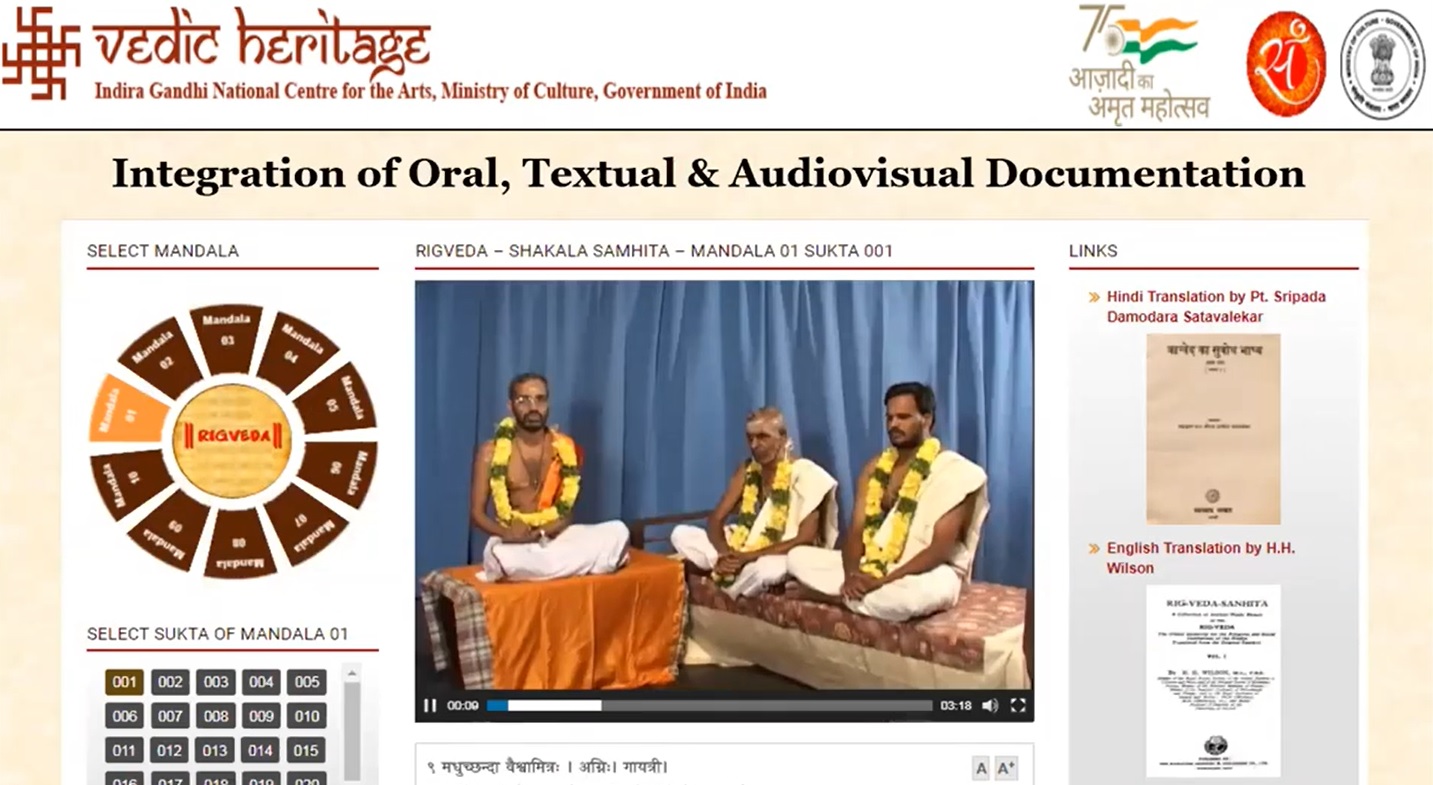

The Eternal Vedas

Sudhir Lall is presently the head of the Kalakosa Division and project director of Bharat Vidya Prayojana, Vedic Heritage Portal, and Nari Samvaad Prakalp. His session focused on the Vedas as the fountainhead of Indian Knowledge Systems. Prof. Lall underlined how the Vedic tradition came down to us through oral traditions. This huge corpus being transmitted across generations is a remarkable story in itself. The result of this unbroken tradition is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s 2003 proclamation of Vedic chanting as an ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.’

The session highlighted the contribution of Indian mnemonic techniques to this transmission process, showed examples of this rare but living tradition of Sanskrit, and explained how techniques like the Prakriti and Vikriti paatha have been instrumental in maintaining this flawless oral transmission.

Engaging with Sanskrit

Anuradha Choudry, a coordinator for the IKS Division of the Ministry of Education (Government of India) and a faculty at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, delivered sessions about her journey with Sanskrit, its rewards, and challenges. She highlighted that the etymology of Sanskrit is samyak kritam (well done), and a closer inspection reveals how its features reflect an inherent perfection of expressions. In her words, “Language is a powerful tool of human communication; our general understanding is that it is shaped by the user and their nature. However, a lesser recognized fact is the extent to which language shapes its user. It is in this context that we attempt to explore the nature of the Sanskrit language. My journey with Sanskrit started as a living language when I was a student, and teaching Sanskrit in Sanskrit has been a fascinating journey for me.”

Ayurveda and Sanskrit

U. Indulal has been active as chief editor of Abhinava Dhanvantari, a journal of Ayurveda published by PNNM Ayurveda College, executive director (operations) of Akami Ayurveda Hospital and Research Center, and dean (academics) of Swiss Med School, Geneva. His lecture mentioned how shabda pramaana (verbal testimony) carries the traditional Indian medical knowledge of Ayurveda. A Sanskrit medical text must be correctly understood by the vaidya (traditional practitioner of Ayurveda) to make accurate clinical decisions. The clarity, efficacy, and scope of Ayurveda tenets happen through a thorough search and research in the mind of the vaidya. The validity of a medical explanation lies in its affiliation with a textual reference. Thus, each content in an Ayurveda text is revered as a mantra, and reciting it daily is a ritual. In olden-day Kerala, the first fifteen chapters of Ashtaangahridaya, an Ayurveda text that presents medical knowledge as a poem, were taught to young non-medical students to help them learn Sanskrit and use the knowledge gained to lead a healthy way of life. The lectures introduced Ayurveda medical texts in Sanskrit, their structure, study methods, how Sanskrit and our understanding of the texts enable an effective application, and what we miss in the process of their translations.

Sanskrit Drama in Theory and Performance

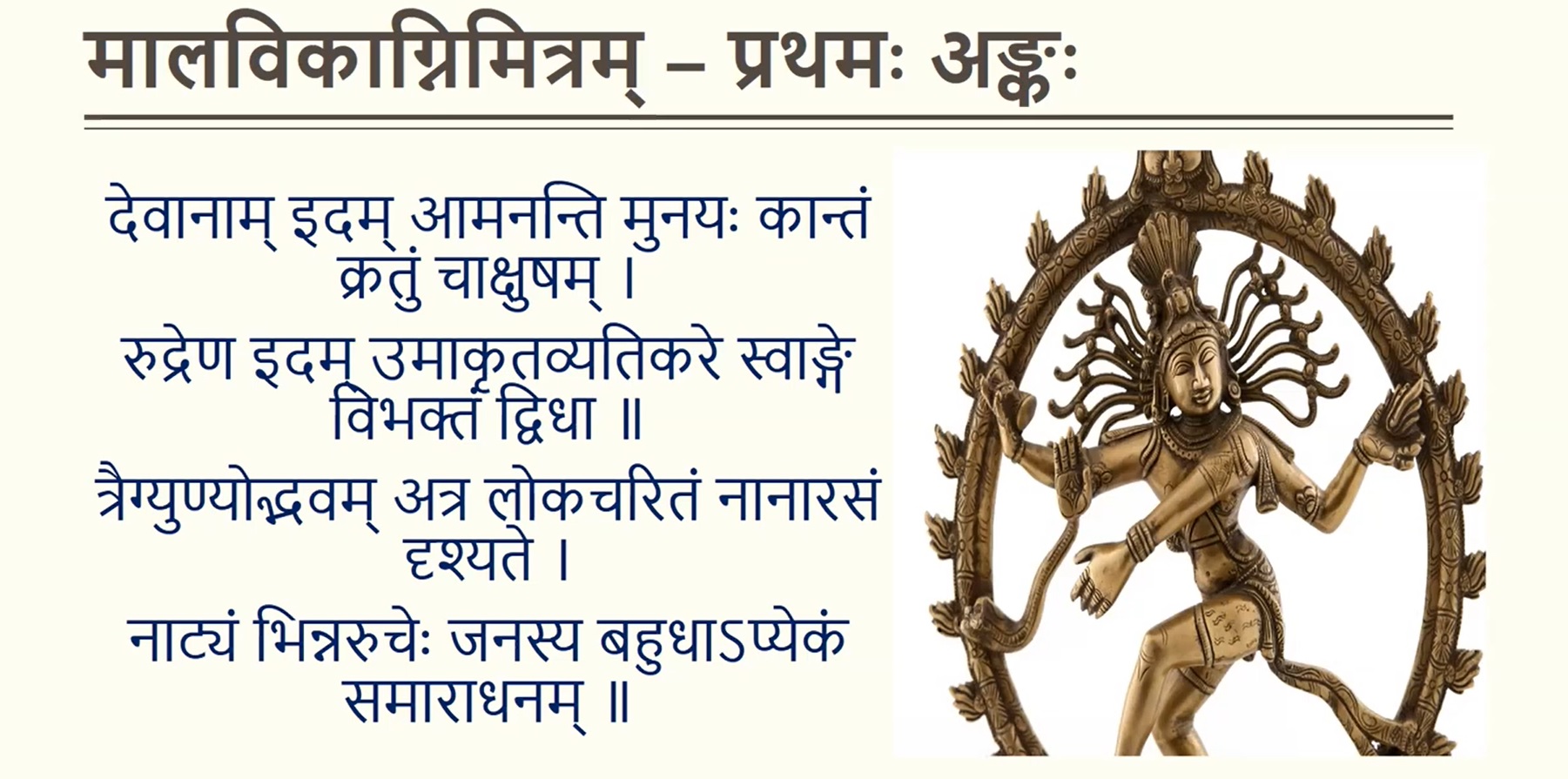

Prasad Bhide earned his doctoral degree from the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay with a dissertation in modern Sanskrit lexicography and is working as an assistant professor at K. J. Somaiya College of Arts and Commerce, affiliated with the University of Mumbai. His talks focused on drama as a performing art that has been a special feature of Indian culture and comprises a significant part of literature in Sanskrit.

Prof. Bhide discussed the theoretical aspects of drama as documented in the text called Naatyashaastra, which begins with a legend about the origin of drama, to illuminate the idea of audio-visual media in Indian knowledge tradition. The session also involved a demonstration of some core parts of the performance of Sanskrit drama with reference to Kalidasa’s celebrated play, Abhigyaana Shaakuntalam. There was a discussion about the challenges in staging Sanskrit dramas during the present times and the way forward.

Sanskrit, and the Essence of Yoga Tradition and Practice

Vinayachandra Banavathy is the Director of the Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems at Chanakya University and a co-founder of Indica Yoga, a platform that offers transformative yoga training. In his words, “With a modest beginning as a discipline of personal and spiritual growth, today Yoga — a living tradition in the unfolding of the Indian civilization — has reached every corner of the world and has touched and transformed millions of lives. A broad term for various practices guided by a set of principles united in spirit, its interpretations vary from simple relaxation techniques to the experience of profound realizations.” His lectures examined some key concepts, frameworks, texts, and terminologies that inform the philosophy and practice of Yoga. It is important to note that from the text of the Yogasootra to the names of aasanas, much of this literature is available only in Sanskrit, also considered the lingua franca of Yoga.

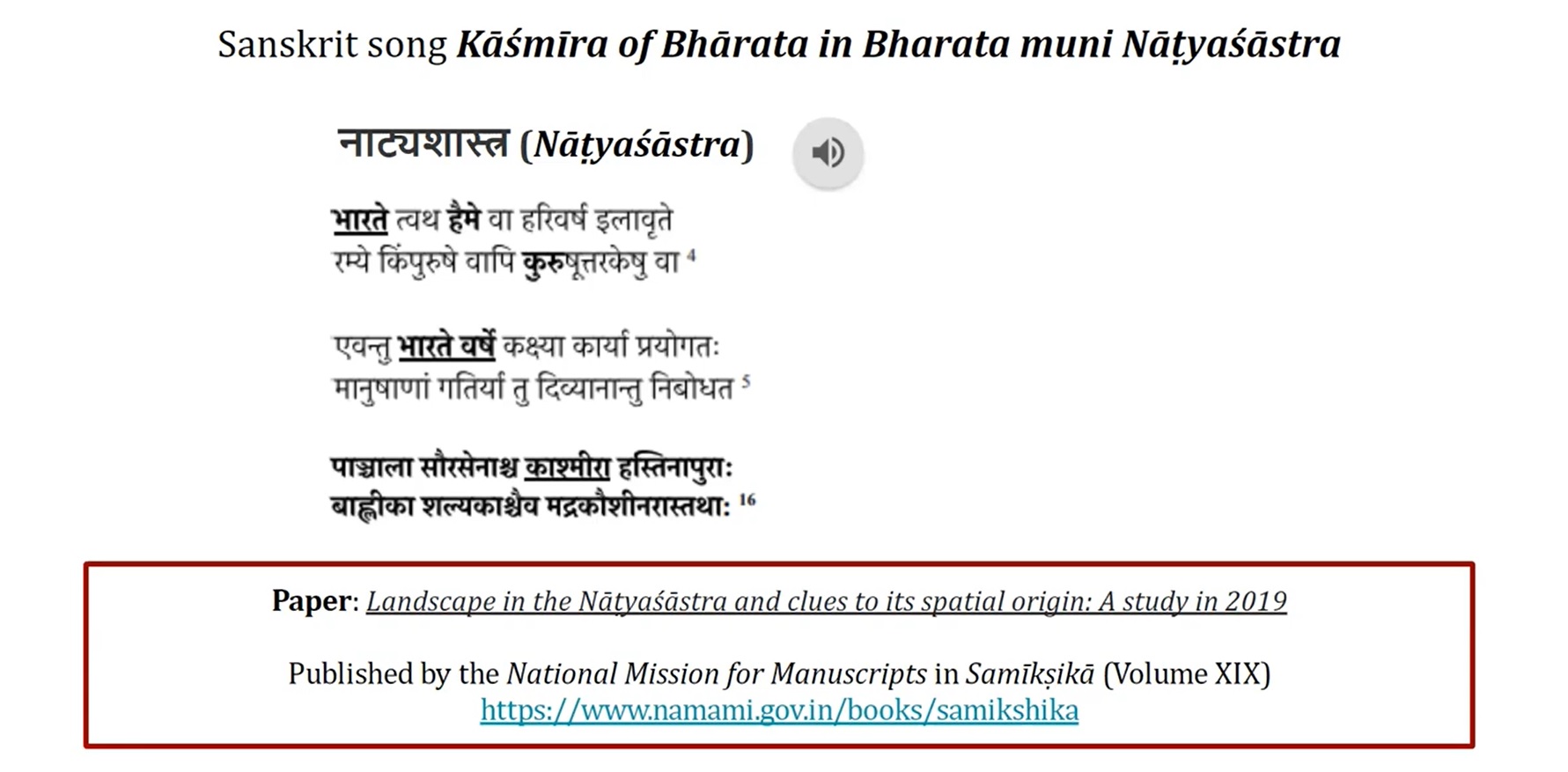

Some Reflections on Sanskrit’s Vitality and Role

Megh Kalyanasundaram is the Director of Special Projects at the Indica Classical Library (ICL), with academic writings spanning aspects of ancient Indian chronology, the landscape in Indic texts, ancient Indian jurisprudence, and ideas of India, to name a few. His talks revolved around important questions: Have any new and original works been published in Sanskrit after it was supposedly pronounced dead? If yes, which is the most comprehensive published bibliography of original modern Sanskrit literature?

Are there any distinctive trends in contemporary Sanskrit publications? He discussed answers to such questions from published sources and invoked the role of Sanskrit as “the Great Integrator”, as observed by the renowned Sanskrit scholar Dr. V. Raghavan. The talks also dived deeper into important facets of this idea with the help of some recent Sanskrit music albums.

The Humanities and Social Sciences discipline at IIT Gandhinagar initiated a semester-long IKS course in 2016 intending to gain and spread a deeper understanding of India’s knowledge traditions. Through the years, this course has attempted to decipher shared Indian concepts in diverse fields by organizing curated lectures from distinguished academicians and has successfully completed seven editions. The seventh edition of the IKS course, from January-April 2023, was conducted in a hybrid mode, open to students from anywhere interested in studying Indian knowledge systems. Videos of lectures from previous editions are available online and are currently being transcribed to build a repository of resources on the Indian knowledge systems.

This story has also been published on Medium.