STORY CREDITS

Writer/Editor: Apeksha Srivastava

Photo: Media and Communication, IIT Gandhinagar

“Literature is a comprehensive essence of the intellectual life of a nation.” — William Shakespeare

As a part of the lectures series under the Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) elective course, the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar conducted two online lectures, ‘Sweeter than Honey: The Advent and Rise of Classical Telugu Literature’ and ‘Conquest of the World: Krishnadevaraya’s Āmuktamālyada.’ Distinguished author, translator, and musician Dr Srinivas Reddy delivered these talks on January 20 & 21, 2022.

The first lecture provided a glimpse into Telugu literature’s interesting history of language, identity, and region. Dr Srinivas highlighted a relatively new idea of Telugu as a language being embodied as a feminine deity. Proceeding further, he said, “Telugu was the locus where the whole regionally defined state mandates began in India.”

Tracing the Word

There are several conjectured origins of the word ‘Telugu.’ One of them involved Trilinga, the three great Shivalayas (coastal Andhra, Telangana, Rayalaseema) that mapped out a specific territory. It outlines the three central regions within the Telugu-speaking zones at some level. Another derivation traced the word to teně, meaning honey and suggesting that Telugu is sweet like honey, as in the title of the first lecture. A third is supposed to come from Tělěgas, a tribal people speaking this language. Dr Srinivas mentioned that Śrināthā, one of the great Telugu poets around 1400 CE, was an itinerant poet who served different kings. His itinerancy, in many ways, marked out the Telugu-speaking land: “Śrināthā was an interesting character in being able to define what is Telugu by traveling to different places.”

Telugu & Sanskrit: A Fascinating Relationship

We cannot separate Telugu literature from Sanskrit: much of the Telugu literature is defined by models derived from Sanskrit (e.g., grammar). The tools through which we define ourselves are derived from a culture of perceived prestige. For instance, the bulk of the privileged scholarship in South Asian studies is not in any Indian language but in English.

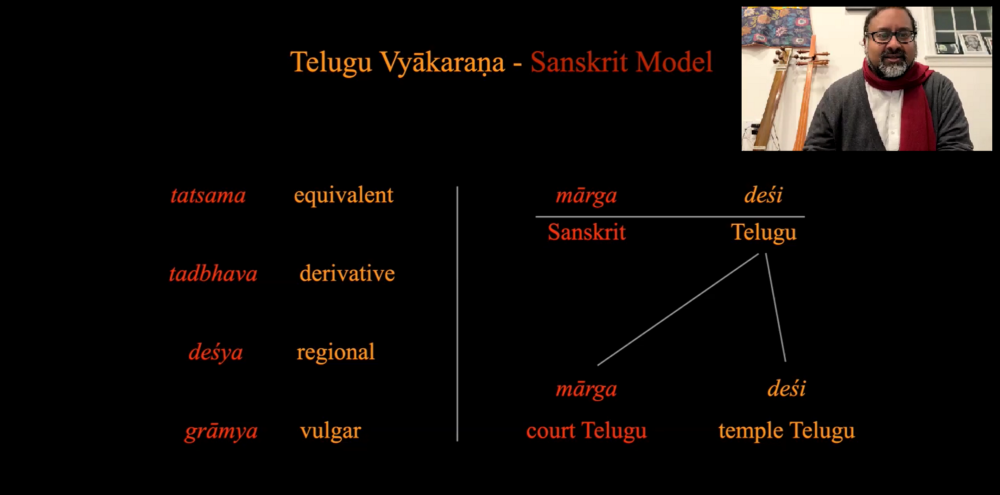

Words from Telugu vyākaraṇa can be divided into four broad categories:

The first contains words equivalent to those in Sanskrit (tatsama). Words in the second category are similar to ones in Sanskrit but have gone through some intermediary morphological change (tadbhava).

The third consists of regional words that sometimes ‘get’ a Sanskrit origin put on top of them (deśya). The last category includes purely regionalized words, removed from Sanskritic influence, and are not acceptable for literary usage (grāmya).

Dr Srinivas also elaborated on the concept of ‘marga’ and ‘desi.’ At the beginning of Telugu literature, Sanskrit (pan-Indian elite tradition) was the marga, and Telugu was desi (regional). However, by Krishnadevaraya’s time, marga and desi started defining different kinds of Telugu literature. So, marga Telugu was used in courts of kings and followed the Sanskrit models, whereas desi Telugu used less Sanskrit forms. With the evolution of time, therefore, an initially ‘desi’ line of literature rose to ‘marga’ or classical status.

The Advent of Classical Telugu Literature

Explaining the advent and rise of classical Telugu literature, Dr Srinivas stated, “We have to understand that the stories we hear are built-up over time to tell a certain narrative about how a language evolved.” The tale of Adikavi Nannaya presenting his Telugu version of the Mahābhārata (Āndhra-Mahābhāratamu) to Rājarājanarendra in 1050 CE illustrates how there was a certain level of prestige attached to a text like the Mahābhārata, attracting anyone who wants to start a literalizing process in a region. Dr Srinivas also discussed renowned poets like Somanātha and Potana. The stories told about them represent different strands within the Telugu literary tradition.

The multifaceted process of vernacularization is a theme associated with the advent of any literature. Vernacularization is the historical process of choosing to create a written language, along with its complement, a political discourse, in local languages according to models supplied by a superordinate, usually cosmopolitan, literary culture (Pollock 2006: 23). Another theme is cosmopolitan regionalism, a type of hegemonic functionality that culturally persisted for hundreds of years in many parts of South Asia and beyond, profoundly related to the Sanskrit language itself. Both themes are an integral part of classical Telugu literature. Dr Srinivas concluded the first lecture by providing insights into Telugu Chandas, the study of poetic meters and verse.

Conquest of the World

The second talk threw light on one of the Pancha-Mahākāvyas (five great poems) of Telugu, the Āmuktamālyada penned by the sixteenth-century Vijayanagara king Krishnadevaraya. Dr Srinivas started by highlighting that Krishnadevaraya’s texts hint towards his practice of and deep connection to Sri Vaishnavism (goddess Lakshmi and god Vishnu are together revered in this tradition).

The period of the Vijayanagara empire is sometimes called the Golden Age of Telugu literature as the majority of the courtiers were Telugu poets, especially eight of them (aṣṭa-dig-gaja) sitting in a great hall called ‘Conquest of the World’ — which refers not to military conquest, but to poetry’s power to conquer the universe. (There are references even from Portuguese sources to this great hall.)

Dr Srinivas expressed, “Literature was a media outlet during those times — there were no radio, television, or social media platforms. Poets spread the words of the King. The fundamental Indian idea of poetry is based on the ‘word’ being generative of the universe. It indicates the immense power of crafted sounds and words like poetry for people and societies.”

Āmuktamālyada: The Story

At one level, Āmuktamālyada is a continuation of the tradition growing since the times of renowned poets like Nannaya, Potana, and Śrināthā. On another level, it is a very interesting and critical departure from some of the earlier trends of Telugu literature.

The context of this poem involves Krishnadevaraya on his quest to conquer the Kalinga territory. At one point, he camps near the Andhra Maha Vishnu temple. He dreams of god Vishnu telling him to write something in Telugu.

Before this poem by Krishnadevaraya, almost all Telugu literature was primarily based on stories from the Sanskrit tradition (e.g., Mahābhārata, Ramāyana, the Purānas). Krishnadevaraya departed by composing a story drawn from the Tamil tradition instead of Sanskrit, written in ornate classical Telugu.

Āmuktamālyada, meaning ‘the girl who gave the garland away,’ extols the Tamil Alwar saint Andal and her devotion to Krishna, weaving together themes relating to vernacular literature, courtly power, and bhakti. It is what situates Krishnadevaraya within the Sri Vaishnava tradition.

Dr Srinivas also briefly discussed the six chapters of Āmuktamālyada. He emphasized that a Mahākāvya starts with a little kernel, a small story that is a pre-text for the Mahākāvya to discuss different themes and teachings.

Distinctiveness & Amalgamation

A significant portion of the Alwar tradition that Krishnadevaraya was exposed to filtered through Ramanuja’s work, involving a certain kind of Sanskritization of that Tamil tradition. Krishnadevaraya was a Tulu, who composed literature in Telugu and Sanskrit, but generally, he is called the King of Karnataka (kannaḍa-rāya). All these aspects highlight the beautiful amalgamation of several literary traditions, stressing at the same time the magnificence of their individual components. Dr Srinivas explained how these traditions evolved over time and how perceptions about languages, their status, functions, and interactions, also keep changing over time.

Both lectures included recitation of selected verses and concluded with lively Q/A sessions. The fourth and fifth lectures of IKS 2022 will be given by Dr. Kapil Kapoor (formerly JNU, New Delhi) titled The Landscape of Indian Literatures on 27th January, and Shah Hussain: 16th-Century Punjabi Sufi Poet on 28th January 2022 at 5:05 pm IST. IKS 2022 is open to students from anywhere interested in Indian knowledge systems. They can audit it for free by filling out an online registration form available on the website.